Depending on where you live, you may have noticed a wine label named 19 Crimes. (Pictured above). It features a convict sent to Australia on the label. If you download an app and face your phone in front of the label, it will start talking and telling you about the crime that sent them on their way. Until just a few weeks ago, this was an interesting marketing novelty to me. I had no idea there were in fact, Australian convicts in the Wayne ancestry. For those of you who do not share in the Furner (June Wayne) tree branch –hopefully you find the Furner convict stories still worth a read.

Just as I was coming across this detail in the Furner ancestry, I happened to have a text exchange with Cherub and she commented to me that “Nanna” (aka June Wayne) had spoken to her about it. I was stunned! Mom had told Cherub that she came from convicts and had to hide it in school, or she would have been teased. Cherub even remembered the verbatim words: “it wasn’t always cool, it used to be embarrassing”. I am so happy Cherub had that chat to confirm what my Internet searching was turning up. I immediately flashed back to a memory of a spring break trip I took to see Mom, April of 2016. On one particular day it was raining, so we decided to make it a museum day. The first stop was a museum that was new to us both: The Hyde Park Barracks Museum. This is historical site turned into a museum devoted to the history of Australia with a particular emphasis on the convicts. We wandered through that building that had once been a processing center for convicts over two hundred years ago. If you ever had the pleasure of going to an exhibit with June Wayne, you know that we stopped and read every placard at every display. It was a very fascinating place and yet she never dropped one hint of a family connection. Now in retrospect, it just speaks to the stigma it held in her during her school age years of the 1930’s.

I then was curious about the evolution of this shift in attitude towards convict heritage and found an interesting article in the Sydney Morning Herald written in 2019, about the topic and here is one quote that summed up the article: “There was a time, only a generation or so ago, when such matters wouldn’t be discussed in polite society, if at all. Convict shame, however, has become convict chic.”

After reaching out to others it was further revealed that Uncle Geoff (June Wayne’s brother) had also remarked about this to Stan decades ago. Well now you all are in on the secret. But what maybe wasn’t shared with June in those early days are some stories of survival and what I see as resilience that I think are worth sharing.

A little background for those who have not read all the placards at the Barracks Museum (or gone to school in Australia): Fun fact, England had been sending convicts to the colonies in America to alleviate their overcrowded prisons. After those pesky colonists won the Revolutionary War, it put an end to that destination for convicts. So, starting in 1788, England started sending convicts to their new colony in Australia. Not only did it help with the overcrowded prisons, but the convict labor force helped to do some of the hard labor in this new settlement of New South Wales. As you will read, some of the crimes were not serious yet it seemed to be enough to be sentenced to 7 years. Some of the crimes were more severe and earned a sentence of 14 years or even life in Australia.

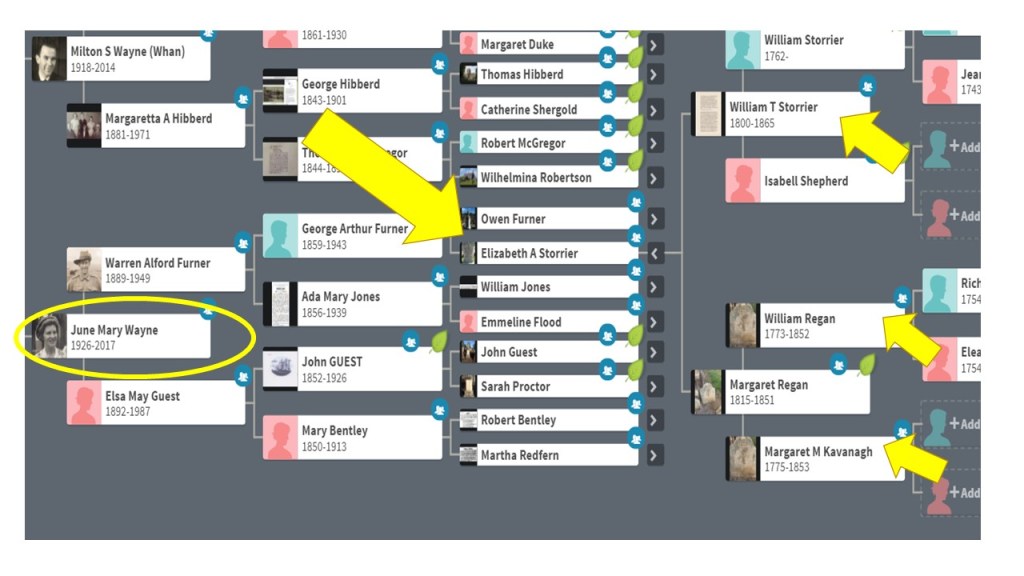

To illustrate where the people of these stories fall in the family tree – take a look at the image below. I circled June Wayne (Furner) so that you can trace back from her on her paternal side.

Following the line from June > her father, Warren Furner>paternal grandfather, George Arthur Furner> then great -grandfather, Owen Furner. Owen came from Brede, England with his parents when he was just 10 years old. There are ship records showing them as assisted or bounty passengers – so not convicts. According to his obituary (I uploaded it to the Photo page) at some point Owen went to Paramatta and apprenticed in a mill. Then when the apprenticeship was over, he went to Goulburn where I can only assume his parents had already settled and began working at Bradley’s Mill before going on to other jobs.

Eventually he would run a store and auction in Goulburn and do quite well for himself. One interesting side story not mentioned in the obituary is that at the age of 21, he married a Sarah Slater, age 20, from Ireland. In the next three years they had two daughters: Mary and Emily. Then tragically at age 29 in 1855, Sarah died. The coroner’s inquest lists cause of death as poisoning, but the how is “unknown”. Two years later, Owen, the 29-year-old widower with two young daughters, marries again in 1857. His bride is a 21-year-old Elizabeth Annabella Storrier, June Furner’s great grandmother. And this is where our convict story begins. Elizabeth Storrier Furner intrigues me, I could spend a lot more time doing more research (and I probably will) but here is the information I have discovered so far:

Elizabeth Storrier was born in the Goulburn area, so she was not a convict. It is her father and both her maternal grandparents that have the intriguing background.

I found the most detailed account for Elizabeth’s maternal grandfather so let’s start with William Regan. He was born in Cork, Ireland, somewhere between 1773 and 1778. Birth, baptism, and other records were handwritten, sometimes with a fancy cursive flourish, so his last name s pops up as Regan, Ragan, Raydon or even Radon. Thus, his exact birthdate is hard to nail down. But what does seem correct is that in 1798, as a young man in his twenties, he finds himself in legal trouble, in London. William is accused grand larceny, stealing one silver tablespoon and three silver teaspoons.

Here is the actual court record from the first witness:

CHARLOTTE NOTT sworn. – I am the daughter of Thomas Nott, I am fourteen years of age: On Monday, the 11th of December, the prisoner knocked at the door of my father’s dwelling-house, No. 4, Fountain-court, Minories, and asked if we had a lodging to lett; I said, yes, and shewed him the room up two pair of stairs backwards; he said, it would do for him very well; my mother was not at home, and he asked me to let him stop a bit till she did come home; I said, yes; and he followed me down into the kitchen; in a very short time, my mother knocked at the door; he took particular notice of the things in the kitchen, and that-gave me rather a suspicion; I thought if he had an opportunity, he would steal something; I opened the door, and told my mother, a young man waited to see her; and I went down stairs with intent to light him up, and I met him half way on the stairs; I did not stop to light him, but went past him into the kitchen, to see if I missed anything, I looked on the tea-board, and immediately missed three silver tea-spoons; I came up, and he was then in the passage, asking my mother, how much she asked a week for the room; I told my mother, the man had got the spoons, and he immediately ran out as fast as he could, through the court; there was a young man coming through the court, who stopped him, and directly as he stopped him, he dropped two spoons, a table-spoon and one tea-spoon, in the court, and I picked them up; when I went down stairs again, to look, I said, there is another tea-spoon wanting, and we found it under the chair where he was sitting; when we found that, I missed another, and he dropped that under the chair; I said, he drops them as fast as I say they are wanting; there was a constable sent for, and he was secured.

The father and mother, owners of the silverware also testify basically the same thing – so we will skip to the prisoner’s (William) defense:

I was just come to London from Romford, and I wanted a lodging, the girl came up, and asked me, if I would see the room, she shewed it to me; when her mother came home, I talked to her about the room, I told her, it was too much money, and I was coming away in a hurry, because I had got a lodging to seek, and I was met by that young man, he stopped me, and said, there was a cry of stop thief, I know nothing at all about the spoons.

Whether he stole the spoons or not, William was found guilty and sentenced to 7 years to be served in Australia. I am not sure of the value of these silver teaspoons but either way, being sent to the farthest reaches of the globe – probably with no hope of returning to his family seems harsh.

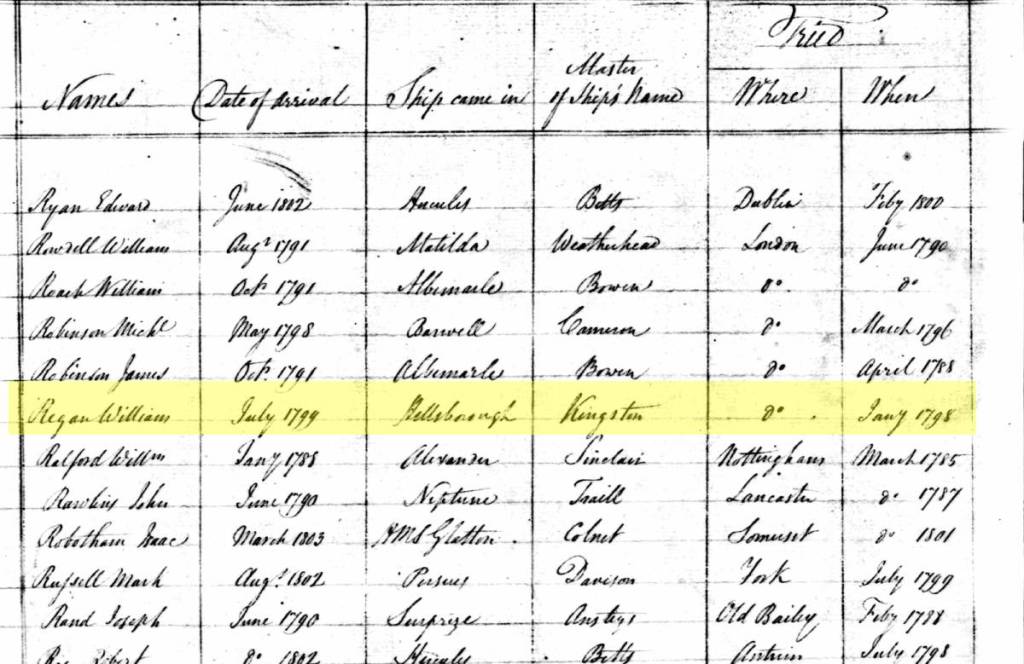

Months later, he was put on the convict transport ship “Hillsborough” which set sail in October of 1798. The ships journey was chronicled by one missionary who was taking the ship as far as South Africa and he wrote of the wretched conditions the convicts were forced to suffer. (link at the end of blog post) This voyage turned out to be one of the deadliest of all the convict transports. 299 prisoners boarded but during the 212 days, ninety-five prisoners died. Most of the deaths were from “jail fever” which spread under conditions of prisoners being shackled together on a deck with little fresh air. So as ancestors of William who suffered through this Hillsborough voyage, we can be thankful he survived and arrived in July 1799.

Once he arrived in Sydney harbor, the next record is several years later where he has already gotten married. (probably around 1805) to a Margaret Kavanagh.

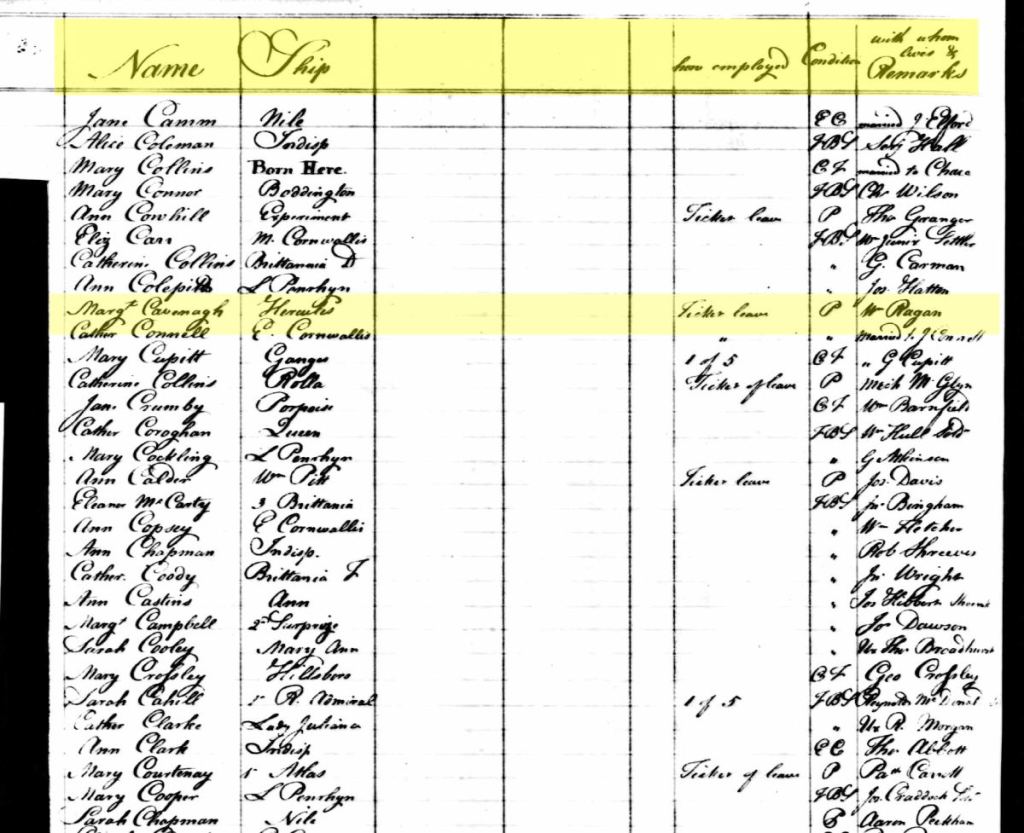

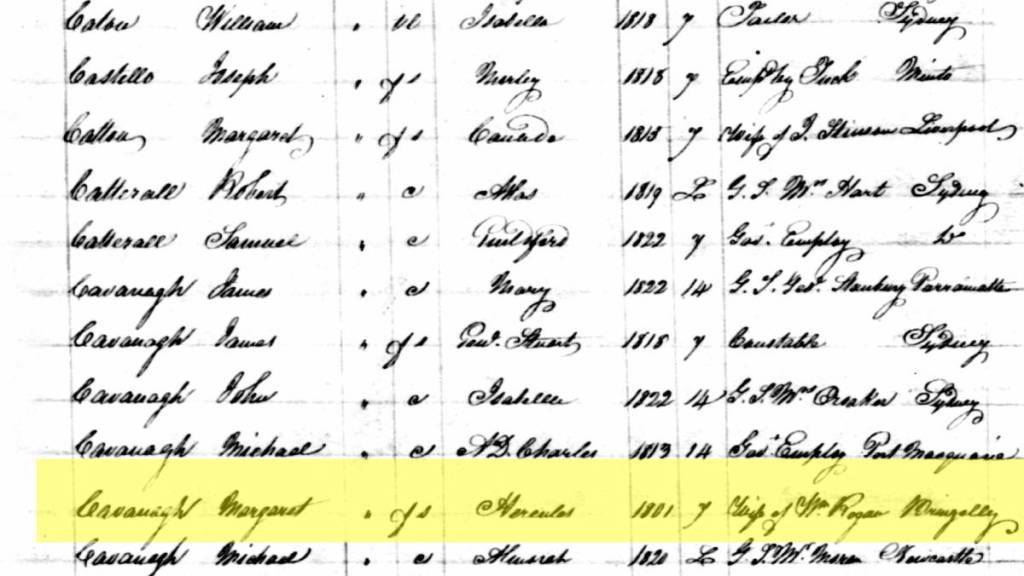

Margaret is from Ireland as well and she too is a convict. Her records are confusing because she gets listed as Kavanagh or Cavanaugh and sometimes Mary Margaret but most likely she was born in Limerick, Ireland. I cannot find her crime, but her sentence was seven years. Historical resources explain that the English were very eager to send women down to the new colony as they were seen as a calming influence on all those convict men – so there is a good chance her crime was very small, and she was found guilty in order to accommodate a need for housekeepers and potential wives in the colony.

Several records showed her ship as the Hercules I, and another shows the Atlas. Doing some digging I found that both ships sailed right around the same time, leaving from Cork, Ireland in 1801. Female convicts were far fewer than males. The Hercules I had 140 men and 25 women. The Atlas 158 men and 28 women. Both ships departed from Ireland late in 1801 and sailed to Rio de Janeiro and then over to the cape (South Africa) and on across the Indian Ocean. (The Suez Canal had not been constructed yet). An exert from a book gives a horrifying account of the Atlas’ and an account of the Hercules voyage shows that it had a mutiny during the trip. So either ship – her experience had to be horrific.

Maybe it is their similar Irish Catholic heritage or maybe because they are both convicts – William and Margaret get together. Here in a convict muster for 1806 we find them both. They are probably married but Margaret continues to be listed by her maiden name through out because the government was always keeping track of convicts.

They have a son, John in 1810 and their daughter Margaret Regan is born in 1815. Convicts had to get permission to marry but I have not found the Regan/Kavanagh record yet. In the 1828 Census there is record of William Regan and his son John both working for a “Bradley” in the Goulburn plain. William is listed as a carpenter.

Convicts were often assigned to work for private farmers. So it could be that William was assigned to work there but after he obtained a ticket of leave or completed his sentence (which would have been by 1806) he continued to work there. I found that interesting because there is a Bradley who apparently owned lots of farmland in Goulburn and employed immigrants as well as convicts with tickets of leave. The Bradley name rang a bell and I realized it is the name of the mill, two generations later, where Owen Furner would work for a period of time.

By, 1831 there is a record of New South Wales Registers of Convict’s Application to Marry for Margaret (the daughter) who is now sixteen applying to marry William Storrier, age 30. She was born in the colony so not a convict but listed here. Possibly because both her parents were convicts she bears the burden of requesting permission. But then another good reason is that the person she is marrying is a convict himself. In the 1830’s it probably was not unusual to marry at the age of sixteen. But I’m also guessing that with both her mother and father as convicts, there would have been a “stain”, so it is not surprising that she marries another convict.

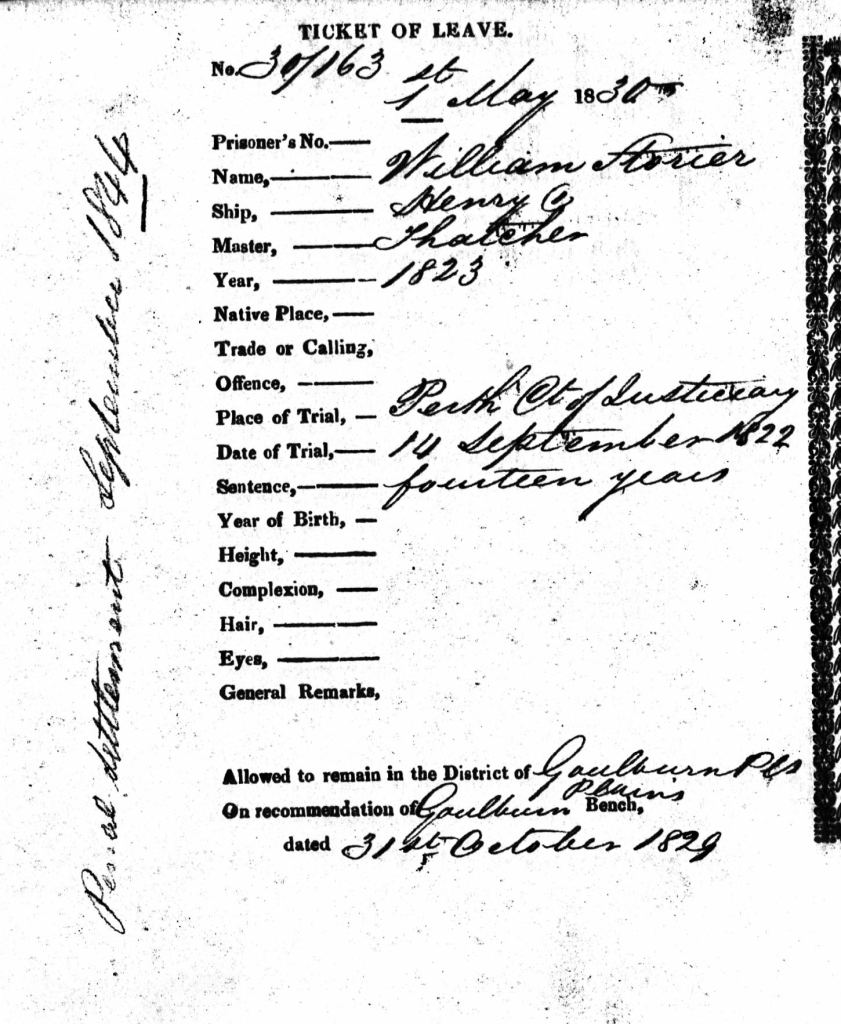

William Storrier was from Dundee, Scotland. There are four generations of Williams in his family, but I am pretty sure I have the right records. In 1822 William (age around 22 years old) and another guy were charged with a more serious crime; assault. They both are sentenced to 14 years “transportation” at the Perth (Scotland) court. He departs on the “Henry” in April 1823, arriving in New South Wales on August 26, 1823. His occupation is listed as butcher. On paper he does not sound like a great guy but at least he earned a ticket of leave six years later. A ticket to leave is like what we would call “probation” and was earned by working hard and staying out of trouble.

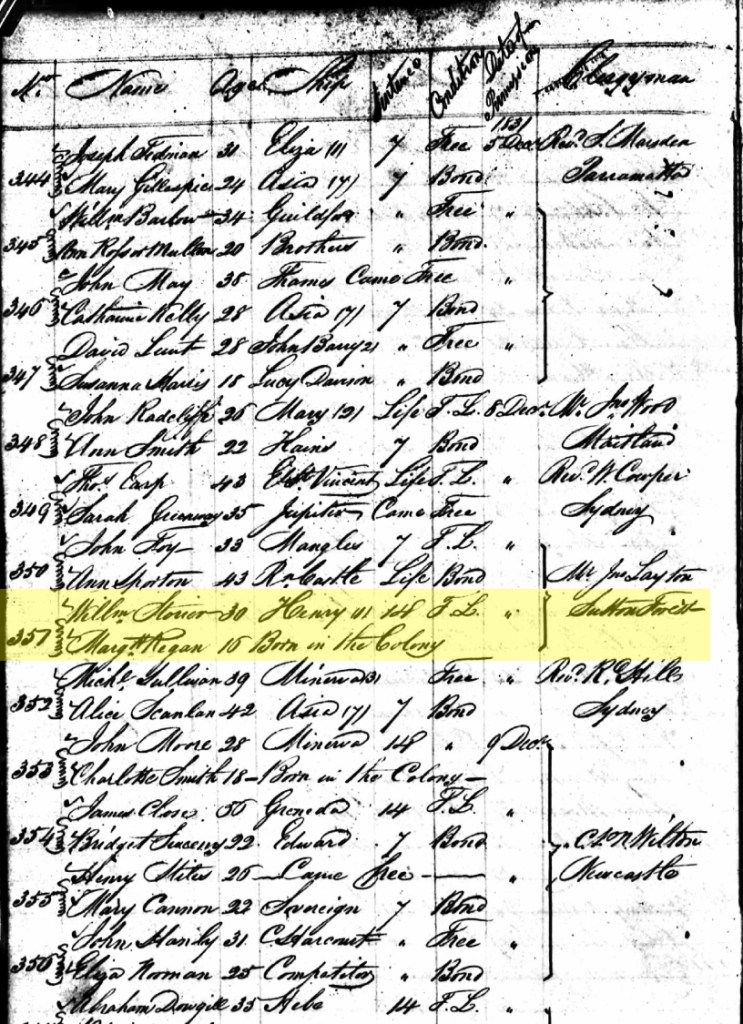

Margaret Regan and William Storrier get married in 1831. They then have a son, William in 1833 and then their second child is Elizabeth Storrier, born in 1836. Her mother was only 21 at the time!

Margaret sadly died at a very young age of 36 in 1851. It feels so tragic and I am still trying to find some more information there as to what was the cause. Her daughter, Elizabeth is just 15 years old at the time.

Margaret Regan Storrier’s headstone is shared with her father – not her husband. But I believe this is because she and her father are buried in the Catholic cemetery. On several of the convict musters, William Storrier is listed as “Church of Scotland”. Her father, William Ragan died only a year after her death in 1852 and then her mother (Margaret Kavanagh Regan) a year after that in 1853. Margaret’s brother John Regan (Elizabeth’s uncle) does live on to the age of 79.

William Storrier, Elizabeth’s father died in 1856. I also am still looking for more details on his life in his later years. Elizabeth’s older brother William Storrier (Jr.) lived in Goulburn, married and had many children – at least 8 or 9 but I haven’t finished that research ha ha.

So circling back to the beginning of this post, in 1857 a year after her father’s death, Elizabeth is 21 and she marries Owen Furner, the widower with two young children. They go on to have seven more children. One of those is June’s grandfather, George Arthur Furner. Elizabeth seems to become an integral part of Goulburn life. Her husband runs the auction house and her siblings remain and thrive in the area.

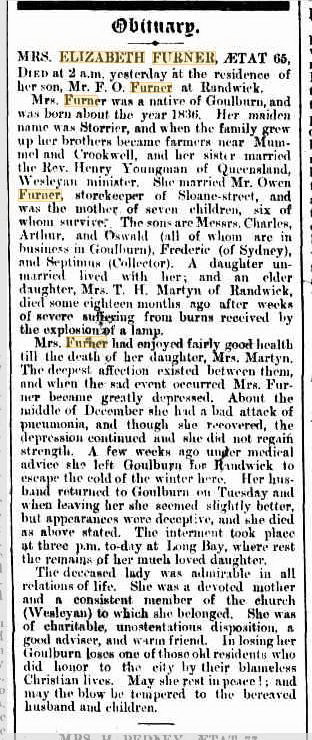

Elizabeth died at age 65 in 1901. I’ve included her obituary (it has another tragic story) but if you don’t read the whole thing, I will add this little inspiring part that is heartwarming: “She was of charitable and unostentatious disposition, a good advisor and warm friend. In losing her, Goulburn loses one of those residents who did honor to the city by their blameless Christian lives”. I think had Mom had a chance to read that and learn more about her, she would be quite proud of her great grandmother, her convict past and all.